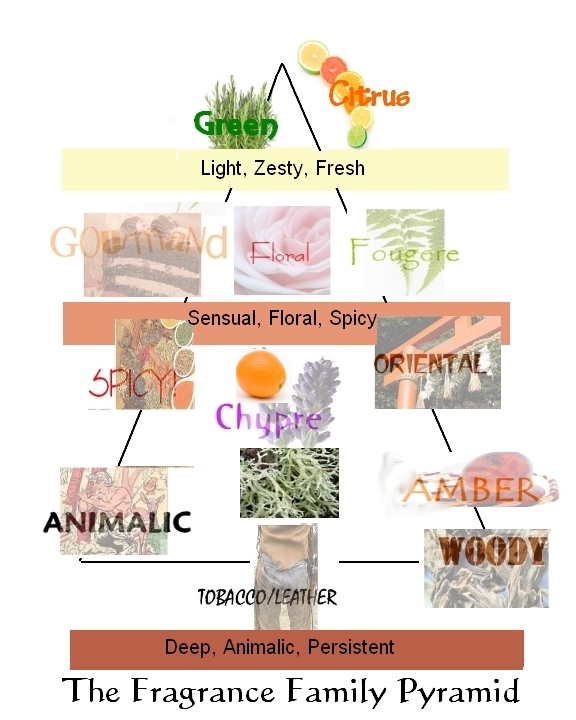

The concept of pyramid of notes was born at the beginning of the 20th century and divides the way a perfume evolves into a thin and quick opening, a larger middle, and a wide base. Volatility is the key word here: the opening notes will be given by the most volatile molecules, whereas for the base they will remain hidden for a couple of hours before waking up and releasing their fragrance.

The opening notes usually last a couple of minutes and I’ve always found them to be the trickiest part. They are the perfume’s introduction, and often its sales pitch. Perfume companies know that many buyers don’t have the patience to wait for the perfume to develop on their skin before deciding to buy it, so they will work hard to make the best first impression ever. Disappointment might come later though.

Sometimes the opening notes are extremely fugacious, and one really has to be quick to capture them. In some perfumes, the opening is five minutes of total molecular chaos, with notes showing up and disappearing like crazy (to me, it’s always a lot of fun when that happens). In the heart notes, the perfume settles down and really starts to talk, expressing its personality. It’s the longest part, and the one where most the evolution takes place. Finally, the so called dry down (or base notes) is where the perfume takes leave and (most of the times) tones down its voice and rounds off the angles.

Having said that, there’s a problem: tastes and techniques in perfumery have greatly evolved in the meantime, making the image of a pyramid at least partly obsolete. There are different ways a perfume can develop, and although perfumers still have to play with volatility of the ingredients on the time continuum, you would hardly find any fragrance offering a neat, three-fold structure nowadays.

For example, some fragrances change very gradually (like Lolita Lempicka’s first perfume, or Light Blue for women by Dolce & Gabbana), some have virtually no heart or base notes (Antaeus by Chanel would be one). Some keep their voice until the end, but change the tone (like Fleur d’Oranger by L’Artisan Parfumeur), others relentlessly change from note to note, forth and back, like in a merry-go-round (I Love Love by Moschino is very good at that).

Yet, we shouldn’t be too quick in dismissing the pyramid as a relic from the past: perfumes, after all, do evolve, and the beginning is almost never like the end. If we give up the idea of having clear lines, a division into opening, heart, and base notes, can still be useful. We, as perfume wearers, can still try and organize the olfactory space (time, actually) occupied by perfumes to understand them better. It’s our right and necessity, regardless of the real intentions of the perfumer.

After all, professionals do the same. The Fragrance Wheel, a perfume classification which is widely used in the industry, uses the dry down as a reference, thus implying a division in different stages. For my perfume blog I personally use the heart notes. I first used the Fragrance Wheel as well, but I started to have doubts when, according to it, I should have categorized that gourmand candy floss blast that goes by the name of Angel (by Thierry Mugler), as a “woody oriental,” and that’s not what Angel is about.

The ultimate goal here is to understand a perfume’s personality and discourse, so if the image of the three-fold pyramid makes your life easier, use it, else leave it. Yet, even in that case, you should still expect a perfume to evolve, like a story unfolding under your nose. And like all stories, some are boring some very interesting, some are linear, some offer weird twists of the plot, some have a great opening scene but later disappoint, whereas for others the heart notes are worth the wait.

{Check out Andrea’s perfume blog for reviews about the perfumes mentioned in the article and many more.}

Image credits: Anya’s Garden

1 comment

[…] Fragrance pyramid-2: http://www.lacedivory.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/FragranceFamiliesPyramid.jpg [in http://www.lacedivory.com/blog/2012/05/12/guest-post-an-introduction-to-the-different-notes-in-a-fra… […]

Comments are closed.